by Marina Marinez

For decades, the highest deforestation rates in Brazil have been recorded at the eastern and southern edges of the Amazon rainforest. In this region, long dubbed the “arc of deforestation,” the conversion of primary rainforest into cattle pasture and soy monoculture, has been the status quo.

In 1999, a group of French and Brazilian organizations teamed up to confront that land degradation and deforestation trend. They launched an innovative reforestation and carbon sequestration project on a former cattle ranch in Cotriguaçu municipality, in Mato Grosso state, at the heart of Amazon’s arc of deforestation, introducing environmentally sound land use practices.

Despite setbacks along the way, the project is thriving today, offering its lessons learned — along with its ongoing scientific assessments and data set — as an example to others. Over the years, it has successfully strived to reforest 2,000 hectares (4,943 acres) of former cattle pasture, planting denuded soils with around 50 species of Amazon tree.

The project implementation on the ground was funded by Peugeot, the French car manufacturer, and by the French National Forest Office (ONF), a state-owned company. This 23-year-old initiative is managed today by ONF Brazil, and receives technical support from several Brazilian and international scientists from the Federal University of Mato Grosso, the National Institute for Amazonian Research, and the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development among other institutions.

Initially, the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project aimed to “test the forest carbon sink concept,” a Clean Development Mechanism generated by the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement to establish binding commitments for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gases emissions, says agro-economist and ONF Brazil manager Estelle Dugachard.

As the project matured, it became a living laboratory in which to observe the dynamics of forest restoration and carbon capture in the Amazon.

“It is an unprecedented forest restoration experiment, and we study it for that reason,” said Thiago Izzo, with the Postgraduate Program in Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation at the Federal University of Mato Grosso. Izzo is regularly joined by other university professors who teach field courses at São Nicolau Farm, where the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink Project is implemented.

Regrowing natural forests can help restore vital ecosystem services, such as clean water and healthy soils; improve biodiversity; and create quality jobs in poor rural areas — in addition to fighting climate change. The São Nicolau Farm offers real world examples of these benefits.

A recent study published in Nature found that natural forest regrowth can capture an even higher rate of carbon emissions than previously estimated by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

At São Nicolau Farm, the multi-decade effort to reforest an area the size of nearly four thousand football fields has created new habitat and an ecological corridor for wildlife endemic to the Brazilian Amazon.

“It is evident that biodiversity is returning to the area,” said Izzo, who has supervised masters and doctoral students who have collected data from the reforested area. “Several species of pollinating insects that are very important for agriculture [including native bees and wasps] are reestablishing themselves there, making nests. We have also seen a wide variety of [medium and large] mammals like monkeys, tapirs, wild pigs and jaguars passing by.”

Dozens of studies conducted by researchers from national and international institutions have been carried out at the farm over the years. One study, for example, showed that the reforestation of the 2,000-hectare fragment, boasting more than two million trees of a wide range of Amazonian species, reached a level of biodiversity much more similar to native forest than to degraded pasture in just 10 years.

But, in reforested plots where teak trees (Tectona grandis) were planted, biodiversity restoration did not go so well, said Izzo. That’s because teak trees are “allelopathic,” producing a chemical that prevents other plants from growing around them. Furthermore, teak being an exotic species, has “an unusual characteristic compared to Amazonian plants;” it loses leaves part of the year, creating a very dry environment, which is not conducive for endemic Amazon fauna nor for fire resistance, added the professor.

Dugachard, from ONF Brazil, explained the reasoning of several project partners behind the teak planting: The plan was to test whether growing and harvesting this wood could be economically advantageous, while also creating a controlled experiment for measuring the difference in carbon storage between exotic and native tree species.

Being the only exotic species introduced into the project area, the teak plots were planted separate from others and on approximately 150 hectares (618 acres), less than 10% of the total reforested area. Once harvested, new teak trees or other timber-providing species will be replanted on these plots, Dugachard said.

Combining several forest restoration techniques within the same area, with each having different associated benefits, is an effective strategy, according to Mariana Oliveira, manager of the Forest, Land Use and Agriculture Program at WRI Brazil. Assisted natural regeneration (ANR), for example, is the most used reforestation technique in the Peugeot-ONF project area. It consists of planting trees native to the local biome, with little human intervention afterward. ANR generates tremendous environmental benefits, including a large amount of carbon capture, with low maintenance costs. But the financial return on these restored lands will also be low.

On the other hand, silvicultural or agroforestry techniques, which combine the exploitation of timber or non-timber products with forest conservation, can generate significant environmental benefits, although smaller compared to ANR, but with a higher financial return.

This financial aspect is important for two reasons, says Oliveira: First, because financial sustainability is a determining factor in the success and longevity of restoration projects, and helps to provide jobs and support local rural economies. Second, meeting the growing demand for wood in domestic and foreign markets with sustainably grown and harvested trees helps ensure the preservation of primary forests.

The Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink project, as originally conceived, is planned to last at least 40 years, from 1999 to 2039. In 2011, the initiative was validated by Verra, one of the world’s most used and trusted carbon offset certifiers, and became eligible to trade carbon credits on the voluntary market. Currently, it is in its third verification phase, which will be conducted by an independent auditing entity accredited by Verra.

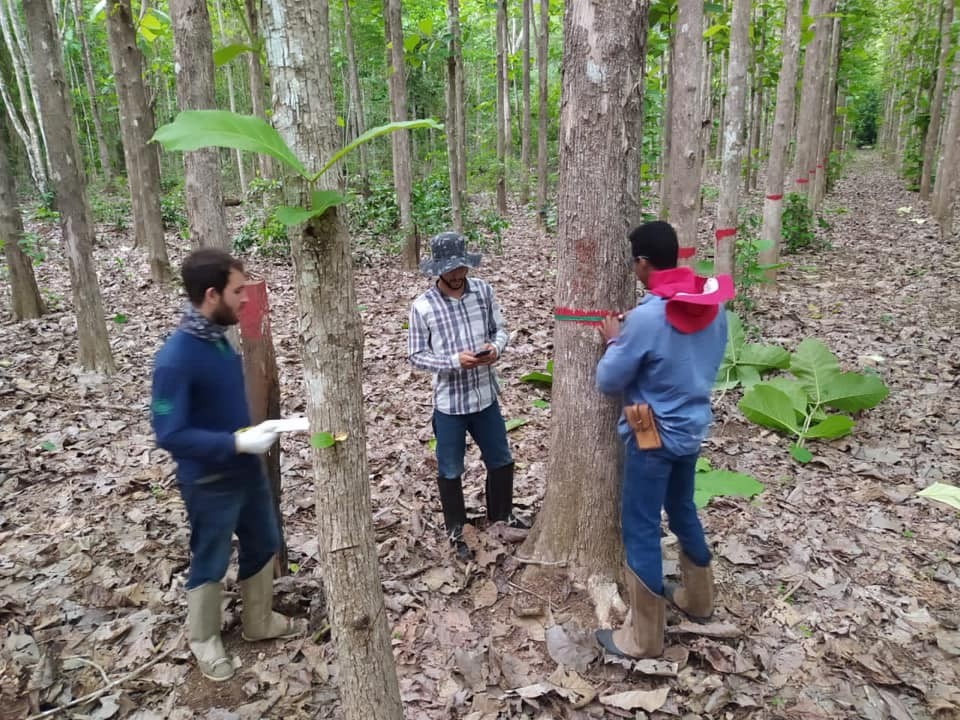

The project measures the carbon stock of planted trees using the methodology recommended by Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard and by the UNFCCC, says Dugachard. “We have more than 400 permanent plots, which have existed since the beginning of the project’s certification, and we measure all the trees in these permanent plots (about 40,000 in total) for biomass monitoring.”

Biomass measurement is the method most recommended by scientists for calculating carbon stock today, says Paulo Nunes, an agronomist who was responsible for estimating carbon fluxes in the project area in its initial phase. He explained that, prior to the project’s certification, the measurement was done using a carbon flux tower installed inside the farm; it measured only CO2 fluxes in the atmosphere and other climatic conditions, providing a less accurate estimate of carbon storage.

Dugachard notes that the ONF Brazil team monitors the biomass of planted trees and takes a carbon inventory annually, even though the inventory is only verified every five years by auditors. This annual assessment is done for “quality assurance,” she said. “After all, a lot changes in the forest in five years.”

A total of 394,400 metric tons of CO2 has already been sequestered by the project — the equivalent of 85,000 cars taken off the road for a year — all of which have been issued as carbon credits. According to ONF’s manager, the carbon stock significantly increased after the first 10-15 years, as planted trees reached maturity, and with the natural regeneration of vegetation.

“The amount of carbon in a restored forest increases as the succession of vegetation advances,” said Euler Nogueira, a Ph.D. in Tropical Forest Sciences from the National Institute for Amazonian Research. However, he added, carbon storage [capacity] gradually decreases after the climax stage is reached. Another point of caution: If major anthropogenic or natural disturbances occur in the restored area, the young forest may begin to emit more CO2 than it sequesters. A forest fire, for example, could undo the initiative’s work overnight, releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere.

The Peugeot-ONF project’s carbon credits are being traded through Pachama, an online marketplace for credits issued by a certifying entity — Verra, in this case. Pachama assesses the integrity of carbon sink projects before they enter its portfolio. “Our team of forest scientists use remote sensing data to identify any sign of harvest or deforestation and assess a project’s additionality, emissions claims and other factors to determine the quality of the project,” the company told Mongabay.

Confirming a project’s “additionality” is critical to the environmental integrity of carbon markets. If an emissions reduction activity would not have happened without a financial incentive, then it is considered additional and eligible for the market. The Peugeot-ONF project, for example, is additional because it is using financial mechanisms to restore degraded land and turn it into a carbon sink, which would not have happened otherwise.

Pachama declined to reveal the entities that have already acquired carbon credits from the Peugeot-ONF project through its marketplace. “As a matter of policy, we do not disclose client investments in individual projects.”

The revenue obtained from the sale of carbon credits is being 100% reinvested in the maintenance of the project, says Dugachard. She told Mongabay that this revenue source is very important for the project’s survival, and was even essential during the pandemic. As COVID-19 raced through Brazil, the São Nicolau Farm had to halt its complementary economic activities, such as ecotourism.

“But the price of carbon on the international market still is not enough to fully pay for a project like ours,” the ONF Brazil manager said, “not least because our choice is to multiply our development activities and our [social] impact on the territory.”

Although the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink does not yet have a SocialCarbon certification, the project team has been working to promote positive social impacts in the rural community.

Students from local elementary schools often take field trips to São Nicolau Farm to learn about environmental issues and the reforestation project. Farmers from neighboring communities are also invited to the farm to learn about agroecology and sustainable forestry practices. According to ONF, around 10,000 people from local communities have already participated in these activities.

“These environmental education activities have had a big impact on the region. It is a rare opportunity for the local population to gain access to specialized knowledge,” says Nunes, an agronomist who has lived for years in Mato Grosso state, near São Nicolau Farm.

WRI Brazil’s Oliveira emphasizes that for restoration projects to work in the long-term, it is important that they act to “improve the quality of life in rural areas,” which goes hand-in-hand with ensuring that “the local population is being involved and heard.”

A settlement of landless farmers, whose incomes depend on the agreements they make with landowners, is located right next to São Nicolau Farm. In an innovative move, ONF Brazil has established a cooperation agreement with these farmers, allowing them to harvest Brazil nuts on the farm to supplement their incomes. In return, these workers help with land maintenance tasks and fire surveillance, Dugachard said.

“First, we mapped the Brazil nut trees inside the farm, involving farmers from the neighboring settlement in this process. Then, they created an association of Brazil nut gatherers, and now they are the ones who manage these nut trees on the farm,” said Nunes, who currently coordinates a network that supports small-scale Brazil nut gatherers in the region called Sentinels of the Forest.

Even though the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink at São Nicolau Farm is clearly achieving successful results, the project is not without risk.

Recent years have seen an increase in environmental crimes in northwestern Mato Grosso state where the farm is located, with the invasion of local properties by timber thieves and illegal miners becoming more common, said Nunes.

The rise in crime has been facilitated by drastic reduction in funding to Brazil’s environmental enforcement agencies, first under President Michel Temer, then with even more dire cuts under President Jair Bolsonaro. Last year’s budget to those agencies was the lowest in 17 years.

State environmental protections have also declined. In the last five years, Mato Grosso authorities guaranteed impunity to two out of five environmental offenders, including in cases of serious infractions, a recent study showed. This year alone, 1 million hectares of Amazon rainforest have already been devastated by illegal fires in Mato Grosso state.

“Our collaboration with local actors protects us,” Dugachard said, when asked about the risks posed to the farm by the rising wave of environmental crime in the region. “But these are lands where the public power itself has difficulty with command and control, so it’s challenging.”

Izzo mentioned another major potential threat: Plans are underway to install a large hydroelectric dam on the Juruena River. If approved and built, its reservoir will likely flood both Indigenous lands and productive areas on the banks of the river — including parts of the São Nicolau Farm.

These threats point up a problem inherent in all carbon storage projects: While they can sequester a great deal of carbon over time, that stored carbon can return to the atmosphere due to environmental disruptions caused, for example, by sociopolitical upheaval.

Then there is the problem of scale. If these initiatives are to capture truly significant amounts of humanity’s CO2 emissions, reducing the existential threat posed by climate change, then they will need to be massively scaled up — and quickly. The hope is that the lessons offered by the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project can be applied across the country and the planet.

Banner image: Amazon rainforest in Brazil. Image by Rhett A. Butler.

Mongabay Series: Amazon Conservation

A maior parte das espécies produzidas são pioneiras (Foto: Acervo da ONF Brasil)

O objetivo é recuperar 120 hectares em 10 anos e a meta para 2017, período da sexta etapa da iniciativa, é restaurar uma nova área de 12 hectares com plantios de espécies nativas e também com o estímulo à regeneração natural. A maioria das mudas produzidas, aproximadamente 70%, são de espécies pioneiras ou secundárias iniciais. De rápido desenvolvimento e responsáveis por melhorar as condições ambientais com a geração de sombreamento, por exemplo, as plantas pioneiras abrem caminho para as espécies secundárias tardias e a comunidade clímax. As principais pioneiras escolhidas para a produção de mudas no viveiro são a Paineira barriguda, Paricá, Mutamba e Ingá. Entre as espécies clímax, destacam-se principalmente o Jatobá, a Castanha do Pará, o Ipê amarelo e o Ipê roxo.

As atividades de restauração nas Áreas de Preservação Permanentes Degradadas (APPDs) da São Nicolau se inserem no Termo de Ajustamento de Conduta (TAC 8607/2012) assinado entre a ONF Brasil e a Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente de Mato Grosso (SEMA-MT). A produção teve início em agosto com o plantio das primeiras sementes, coletadas na própria fazenda, adquirida de coletores do assentamento PA (Projeto de Assentamento) Juruena ou a partir da compra em redes de sementes.

As mudas devem ser plantadas em dezembro, no início das chuvas (Foto: Acervo da ONF Brasil)

Em outubro cerca de 10 mil mudas de 25 espécies já estão em fase de desenvolvimento. Ao final do processo, em dezembro, pretende-se alcançar a marca de 15 mil mudas de 30 diferentes espécies, das quais 11 mil serão utilizadas na Fazenda São Nicolau e as demais disponibilizadas para restauração em outras áreas potenciais, como por exemplo as APPs (Áreas de Proteção Permanente) degradadas às margens do Rio Juruena, no PA Juruena, apoiando o projeto Reflorestamento Afirmativo. A maior parte das mudas estarão prontas para o plantio em dezembro, período ideal para expedição a campo, devido ao início da estação chuvosa.

A iniciativa, realizada em dezembro de 2016, foi a primeira ação do projeto “10x Amazônia” e contou com a presença da sociedade civil, executores do projeto e parceiros. O plantio das espécies nativas doadas pela ONF Brasil ocorreu em uma área da União, às margens do Rio Juruena, no Projeto de Assentamento (PA) Juruena em Cotriguaçu, Mato Grosso. Em 2015, este território sofreu tentativa de grilagem, inspirando então o apoio da ONF Brasil e da Secretaria Municipal de Meio Ambiente de Cotriguaçu (SMMA) com o oferecimento de mudas para o reflorestamento. O coordenador de silvicultura da Fazenda São Nicolau, o engenheiro florestal Alan Bernardes, forneceu as orientações técnicas para o plantio.

O “10x Amazônia”, concebido pelo Promotor de Justiça Cláudio Gonzaga, é um projeto do Ministério Público Estadual de Mato Grosso (MPE/MT) para obrigar os agentes causadores de danos ambientais a repararem a ilegalidade cometida, a fim de recuperar a área desflorestada. O objetivo é executar ações imediatas de combate ao desmatamento por meio da responsabilização civil, criminal e administrativa dos responsáveis.

A atuação do MPE/MT inicia pelas Áreas de Preservação Permanente do Rio Juruena ilegalmente invadidas e deve alcançar as demais regiões desmatadas também ilegalmente. No caso do PA Juruena, os agentes causadores dos danos foram identificados e avisados sobre o mutirão pela Policia Militar.

As ações propostas pelo projeto seguirão o Roteiro de Reflorestamento Emergencial do Bioma da Amazônia Meridional, com orientações técnicas comuns aos Planos de Recuperação de Área Degradada. Portanto, as atividades devem valorizar as espécies nativas da região e o desenvolvimento econômico local.

A intenção em longo prazo é expandir programas com este para toda a Floresta Amazônica brasileira. Desta forma, é possível preservar o bioma e ficar mais próximo da meta prometida pelo Brasil na Cúpula do Clima de Paris: zerar o desmatamento ilegal e recuperar 12 milhões de florestas devastadas até 2030.

Veja a seguir as fotos do mutirão de 17 de dezembro de 2016:

Foto: Acervo ONF/Brasil

Foto: Acervo ONF/Brasil

Foto: Acervo ONF/Brasil

Foto: Acervo ONF Brasil

Foto: Acervo ONF Brasil

Viveiro com as mudas de 38 espécies nativas (Foto: Acervo da ONF Brasil)

Em 2016, as atividades de reflorestamento entraram na quinta etapa do processo de Restauração nas Áreas de Preservação Permanentes Degradadas (APPDs) da fazenda em Cotriguaçu, MT. Foram produzidas 16 mil mudas para o plantio em 12 hectares, que, em conjunto com as ações realizadas nos últimos cinco anos, serão responsáveis pelo cumprimento da metade da meta, já neste ano.

As plantas selecionadas para a iniciativa compreendem 38 espécies nativas, dentre elas o Cedro rosa, a Paineira, a Castanheira, o Jatobá e o Ingá. Além do reflorestamento, outra técnica a ser utilizada para a recuperação da área é a Regeneração Natural, deixando que os processos naturais conduzam ao desenvolvimento livre da vegetação e aproveitando o potencial de regeneração de algumas áreas.

As ações decorrem do Termo de Ajustamento de Conduta (TAC 8607/2012) assinado entre a ONF Brasil e a Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente de Mato Grosso (SEMA-MT). O dispositivo legal determina a restauração nas Áreas de Preservação Permanentes (APPs) da Fazenda São Nicolau a partir de 2012.

De uma forma geral, a iniciativa de reflorestamento no território começou nas áreas de Reserva Legal com o projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF em 1998. Atualmente o TAC de 2012 assegura a continuidade do plantio, agora nas Áreas de Restauração. As ações são necessárias, pois, antes da aquisição da São Nicolau pela ONF Brasil, de 1981 até 1998, a fazenda sofreu com o desmatamento, a queimada e a implementação de pastos. Os diferentes projetos e parcerias firmados pela empresa florestal contribuem para a recuperação e conservação ambiental da área.

A equipe da ONF Brasil trabalha pela restauração de áreas degradadas da Fazenda São Nicolau (Foto: Acervo da ONF Brasil)

Além de promover a preservação do meio ambiente, o reflorestamento também é importante ao produtor rural, tanto no viés econômico, quanto na prática da sustentabilidade.

Foto: BioBlog.

As iniciativas de reflorestamento têm sido essenciais para promover a redução do gás carbônico (CO2) na atmosfera e, consequentemente, evitar a intensificação do efeito estufa. Isso porque a redução do CO2 ocorre devido à fotossíntese realizada pelas árvores, a qual permite que o carbono fixe na biomassa do solo e do vegetal. À medida que a árvore vai se desenvolvendo, o carbono passa a integrar as folhas, troncos, galhos e raízes. Em torno de 50% da biomassa vegetal é feita de carbono. Para se ter ideia, a Floresta Amazônica detém em média 140 toneladas de carbono por hectare.

Mundialmente, o reflorestamento torna-se essencial para minimizar as alterações climáticas e aumentar os recursos hídricos. De forma pontual, há uma categoria que pode usufruir de diversos benefícios ao promover o reflorestamento: os produtores rurais. As vantagens englobam questões econômicas e de sustentabilidade.

Vantagens econômicas do processo de reflorestamento

Pelo viés econômico, reflorestar reflete em ganhos ao produtor rural e não é preciso dispor de muita mão de obra para colocar em prática essa iniciativa que ajuda a embelezar a paisagem da propriedade e valorizar o imóvel. Muitos produtores veem essa alternativa como uma forma de “guardar economias”, isso porque quando necessário é possível comercializar as árvores, depois replantá-las e realizar esse processo de forma sucessiva.

Reflorestar também permite que a propriedade rural fique autossuficiente para a necessidade de madeira. Tendo madeira à disposição é possível dar origem a currais, realizar construções abertas e ter lenha disponível em tempo integral, tudo isso com matéria-prima obtida na propriedade.

Vantagens do processo de reflorestamento ligadas à sustentabilidade

Geralmente as espécies usadas para o reflorestamento se desenvolvem num curto período de tempo, abrindo possibilidade para que elas sejam uma opção de matéria-prima de baixo custo para os produtores rurais. Reflorestar também permite aproveitar as áreas marginais, combater a erosão do solo, maximizar o desempenho das bacias hidrográficas e, ao mesmo tempo, reduzir o impacto ambiental negativo que as culturas tradicionais de plantação geram ao solo.

Soluções biológicas

Essa mesma linha de preocupação ambiental levou a Novozymes, líder mundial no segmento de enzimas industriais e bioinovação, a participar da Conferência das Nações Unidas sobre o Desenvolvimento Sustentável (Rio+20) de forma ativa, integrando as discussões de políticas públicas e de soluções para serem colocadas em prática ao longo das próximas décadas, envolvendo a promoção da economia verde. A Novozymes vem trabalhando incessantemente na formulação de alternativas renováveis para substituir o uso de produtos químicos que tem origem fóssil.

Fonte: BioBlog.

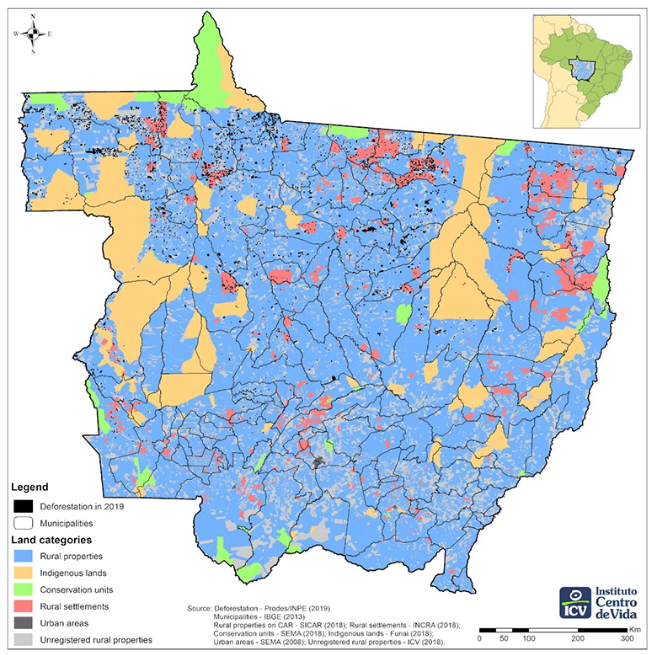

Foto: Raíssa Genro/ICV.

O Núcleo de Geotecnologias do Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV), em parceria com o Laboratório de Sensoriamento Remoto e Geotecnologias da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, produziu no início do mês de julho imagens de altíssima resolução em algumas propriedades rurais de Alta Floresta (Mato Grosso). As imagens, feitas com o uso de um Veículo Aéreo Não Tripulado (VANT), conhecido como drone, podem ser usadas para planejar e monitorar a restauração florestal e as atividades produtivas dos imóveis rurais.

A partir dessas imagens, o ICV produziu um vídeo com o objetivo de mostrar de forma audiovisual o potencial das mesmas. A intenção é apresentar essa tecnologia como algo acessível, em especial na área das geotecnologias, pois através da altíssima resolução é possível planejar e monitorar com maior precisão as áreas em restauração florestal.

O vídeo foi lançado no workshop Movimento Municípios Sustentáveis, que aconteceu em Alta Floresta no dia 24 de novembro. O encontro foi realizado entre representantes de 9 municípios da região com o intuito de constituir um observatório social. Segundo o coordenador do Núcleo de Geotecnologias do ICV, Vínicius Silgueiro, a apresentação do vídeo serviu como subsídio “para mostrar que estão disponíveis essas tecnologias, que os municípios podem inserir a aquisição ou contratação desses serviços em projetos e também pensar na utilização disso para diversas ações de gestão e planejamento”.

Além disso, as imagens produzidas também foram utilizadas para a criação de outros produtos, como uma cartilha e artigos científicos apresentados em eventos. Com previsão de lançamento para o mês de dezembro, a cartilha foi produzida a partir dos resultados de análises feitas com o uso dessas imagens.

Outro produto do Núcleo de Geotecnologias que pode ser uma importante ferramenta para a gestão ambiental municipal é a série de Atlas: Conhecendo Municípios do Portal da Amazônia. A série apresenta um conjunto de mapas e dados dos municípios, com informações sobre o uso do solo, hidrografia, estradas, estrutura fundiária e outros.

Fonte: Instituto Centro de Vida.