by Marina Marinez

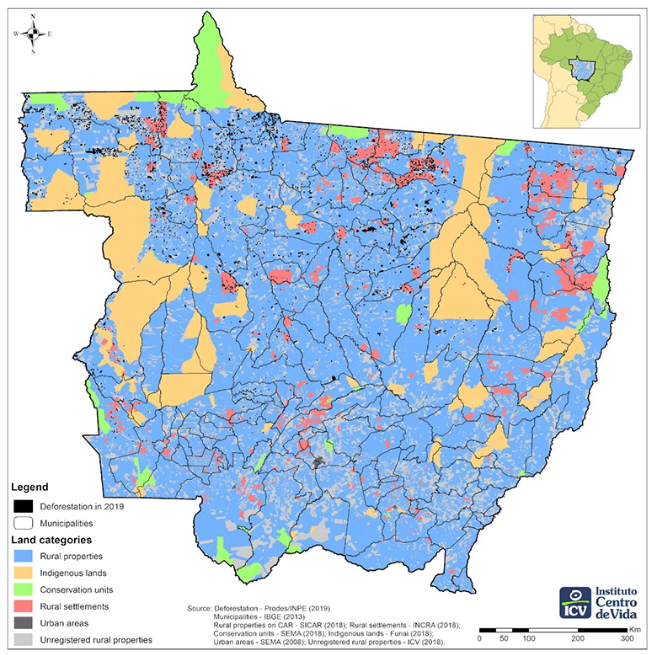

For decades, the highest deforestation rates in Brazil have been recorded at the eastern and southern edges of the Amazon rainforest. In this region, long dubbed the “arc of deforestation,” the conversion of primary rainforest into cattle pasture and soy monoculture, has been the status quo.

In 1999, a group of French and Brazilian organizations teamed up to confront that land degradation and deforestation trend. They launched an innovative reforestation and carbon sequestration project on a former cattle ranch in Cotriguaçu municipality, in Mato Grosso state, at the heart of Amazon’s arc of deforestation, introducing environmentally sound land use practices.

Despite setbacks along the way, the project is thriving today, offering its lessons learned — along with its ongoing scientific assessments and data set — as an example to others. Over the years, it has successfully strived to reforest 2,000 hectares (4,943 acres) of former cattle pasture, planting denuded soils with around 50 species of Amazon tree.

The project implementation on the ground was funded by Peugeot, the French car manufacturer, and by the French National Forest Office (ONF), a state-owned company. This 23-year-old initiative is managed today by ONF Brazil, and receives technical support from several Brazilian and international scientists from the Federal University of Mato Grosso, the National Institute for Amazonian Research, and the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development among other institutions.

Initially, the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project aimed to “test the forest carbon sink concept,” a Clean Development Mechanism generated by the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement to establish binding commitments for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gases emissions, says agro-economist and ONF Brazil manager Estelle Dugachard.

As the project matured, it became a living laboratory in which to observe the dynamics of forest restoration and carbon capture in the Amazon.

“It is an unprecedented forest restoration experiment, and we study it for that reason,” said Thiago Izzo, with the Postgraduate Program in Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation at the Federal University of Mato Grosso. Izzo is regularly joined by other university professors who teach field courses at São Nicolau Farm, where the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink Project is implemented.

Regrowing natural forests can help restore vital ecosystem services, such as clean water and healthy soils; improve biodiversity; and create quality jobs in poor rural areas — in addition to fighting climate change. The São Nicolau Farm offers real world examples of these benefits.

A recent study published in Nature found that natural forest regrowth can capture an even higher rate of carbon emissions than previously estimated by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

At São Nicolau Farm, the multi-decade effort to reforest an area the size of nearly four thousand football fields has created new habitat and an ecological corridor for wildlife endemic to the Brazilian Amazon.

“It is evident that biodiversity is returning to the area,” said Izzo, who has supervised masters and doctoral students who have collected data from the reforested area. “Several species of pollinating insects that are very important for agriculture [including native bees and wasps] are reestablishing themselves there, making nests. We have also seen a wide variety of [medium and large] mammals like monkeys, tapirs, wild pigs and jaguars passing by.”

Dozens of studies conducted by researchers from national and international institutions have been carried out at the farm over the years. One study, for example, showed that the reforestation of the 2,000-hectare fragment, boasting more than two million trees of a wide range of Amazonian species, reached a level of biodiversity much more similar to native forest than to degraded pasture in just 10 years.

But, in reforested plots where teak trees (Tectona grandis) were planted, biodiversity restoration did not go so well, said Izzo. That’s because teak trees are “allelopathic,” producing a chemical that prevents other plants from growing around them. Furthermore, teak being an exotic species, has “an unusual characteristic compared to Amazonian plants;” it loses leaves part of the year, creating a very dry environment, which is not conducive for endemic Amazon fauna nor for fire resistance, added the professor.

Dugachard, from ONF Brazil, explained the reasoning of several project partners behind the teak planting: The plan was to test whether growing and harvesting this wood could be economically advantageous, while also creating a controlled experiment for measuring the difference in carbon storage between exotic and native tree species.

Being the only exotic species introduced into the project area, the teak plots were planted separate from others and on approximately 150 hectares (618 acres), less than 10% of the total reforested area. Once harvested, new teak trees or other timber-providing species will be replanted on these plots, Dugachard said.

Combining several forest restoration techniques within the same area, with each having different associated benefits, is an effective strategy, according to Mariana Oliveira, manager of the Forest, Land Use and Agriculture Program at WRI Brazil. Assisted natural regeneration (ANR), for example, is the most used reforestation technique in the Peugeot-ONF project area. It consists of planting trees native to the local biome, with little human intervention afterward. ANR generates tremendous environmental benefits, including a large amount of carbon capture, with low maintenance costs. But the financial return on these restored lands will also be low.

On the other hand, silvicultural or agroforestry techniques, which combine the exploitation of timber or non-timber products with forest conservation, can generate significant environmental benefits, although smaller compared to ANR, but with a higher financial return.

This financial aspect is important for two reasons, says Oliveira: First, because financial sustainability is a determining factor in the success and longevity of restoration projects, and helps to provide jobs and support local rural economies. Second, meeting the growing demand for wood in domestic and foreign markets with sustainably grown and harvested trees helps ensure the preservation of primary forests.

The Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink project, as originally conceived, is planned to last at least 40 years, from 1999 to 2039. In 2011, the initiative was validated by Verra, one of the world’s most used and trusted carbon offset certifiers, and became eligible to trade carbon credits on the voluntary market. Currently, it is in its third verification phase, which will be conducted by an independent auditing entity accredited by Verra.

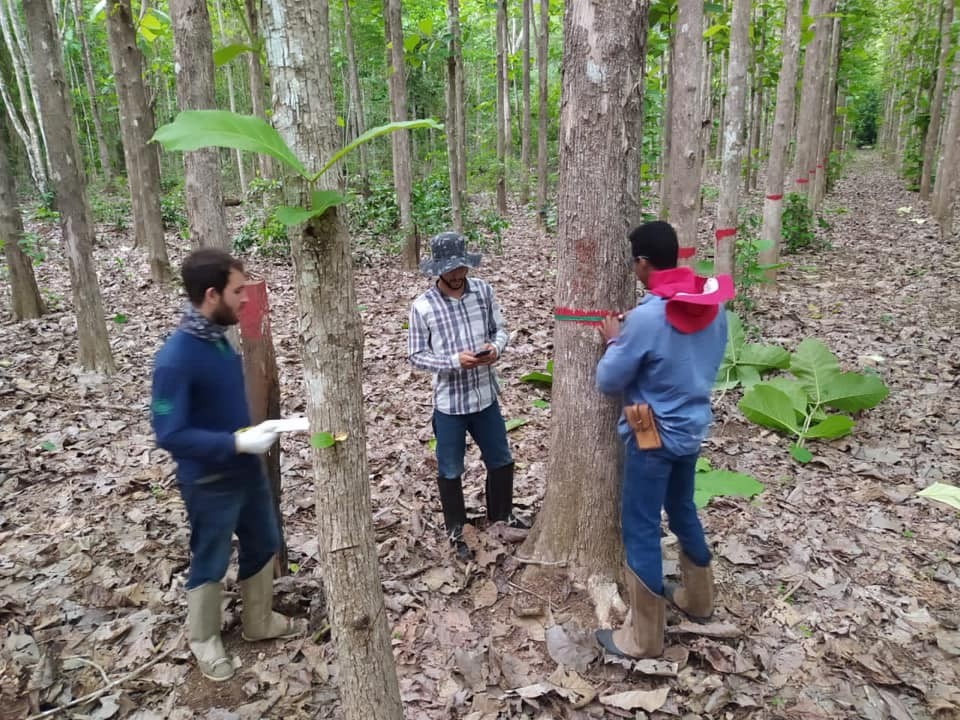

The project measures the carbon stock of planted trees using the methodology recommended by Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard and by the UNFCCC, says Dugachard. “We have more than 400 permanent plots, which have existed since the beginning of the project’s certification, and we measure all the trees in these permanent plots (about 40,000 in total) for biomass monitoring.”

Biomass measurement is the method most recommended by scientists for calculating carbon stock today, says Paulo Nunes, an agronomist who was responsible for estimating carbon fluxes in the project area in its initial phase. He explained that, prior to the project’s certification, the measurement was done using a carbon flux tower installed inside the farm; it measured only CO2 fluxes in the atmosphere and other climatic conditions, providing a less accurate estimate of carbon storage.

Dugachard notes that the ONF Brazil team monitors the biomass of planted trees and takes a carbon inventory annually, even though the inventory is only verified every five years by auditors. This annual assessment is done for “quality assurance,” she said. “After all, a lot changes in the forest in five years.”

A total of 394,400 metric tons of CO2 has already been sequestered by the project — the equivalent of 85,000 cars taken off the road for a year — all of which have been issued as carbon credits. According to ONF’s manager, the carbon stock significantly increased after the first 10-15 years, as planted trees reached maturity, and with the natural regeneration of vegetation.

“The amount of carbon in a restored forest increases as the succession of vegetation advances,” said Euler Nogueira, a Ph.D. in Tropical Forest Sciences from the National Institute for Amazonian Research. However, he added, carbon storage [capacity] gradually decreases after the climax stage is reached. Another point of caution: If major anthropogenic or natural disturbances occur in the restored area, the young forest may begin to emit more CO2 than it sequesters. A forest fire, for example, could undo the initiative’s work overnight, releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere.

The Peugeot-ONF project’s carbon credits are being traded through Pachama, an online marketplace for credits issued by a certifying entity — Verra, in this case. Pachama assesses the integrity of carbon sink projects before they enter its portfolio. “Our team of forest scientists use remote sensing data to identify any sign of harvest or deforestation and assess a project’s additionality, emissions claims and other factors to determine the quality of the project,” the company told Mongabay.

Confirming a project’s “additionality” is critical to the environmental integrity of carbon markets. If an emissions reduction activity would not have happened without a financial incentive, then it is considered additional and eligible for the market. The Peugeot-ONF project, for example, is additional because it is using financial mechanisms to restore degraded land and turn it into a carbon sink, which would not have happened otherwise.

Pachama declined to reveal the entities that have already acquired carbon credits from the Peugeot-ONF project through its marketplace. “As a matter of policy, we do not disclose client investments in individual projects.”

The revenue obtained from the sale of carbon credits is being 100% reinvested in the maintenance of the project, says Dugachard. She told Mongabay that this revenue source is very important for the project’s survival, and was even essential during the pandemic. As COVID-19 raced through Brazil, the São Nicolau Farm had to halt its complementary economic activities, such as ecotourism.

“But the price of carbon on the international market still is not enough to fully pay for a project like ours,” the ONF Brazil manager said, “not least because our choice is to multiply our development activities and our [social] impact on the territory.”

Although the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink does not yet have a SocialCarbon certification, the project team has been working to promote positive social impacts in the rural community.

Students from local elementary schools often take field trips to São Nicolau Farm to learn about environmental issues and the reforestation project. Farmers from neighboring communities are also invited to the farm to learn about agroecology and sustainable forestry practices. According to ONF, around 10,000 people from local communities have already participated in these activities.

“These environmental education activities have had a big impact on the region. It is a rare opportunity for the local population to gain access to specialized knowledge,” says Nunes, an agronomist who has lived for years in Mato Grosso state, near São Nicolau Farm.

WRI Brazil’s Oliveira emphasizes that for restoration projects to work in the long-term, it is important that they act to “improve the quality of life in rural areas,” which goes hand-in-hand with ensuring that “the local population is being involved and heard.”

A settlement of landless farmers, whose incomes depend on the agreements they make with landowners, is located right next to São Nicolau Farm. In an innovative move, ONF Brazil has established a cooperation agreement with these farmers, allowing them to harvest Brazil nuts on the farm to supplement their incomes. In return, these workers help with land maintenance tasks and fire surveillance, Dugachard said.

“First, we mapped the Brazil nut trees inside the farm, involving farmers from the neighboring settlement in this process. Then, they created an association of Brazil nut gatherers, and now they are the ones who manage these nut trees on the farm,” said Nunes, who currently coordinates a network that supports small-scale Brazil nut gatherers in the region called Sentinels of the Forest.

Even though the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink at São Nicolau Farm is clearly achieving successful results, the project is not without risk.

Recent years have seen an increase in environmental crimes in northwestern Mato Grosso state where the farm is located, with the invasion of local properties by timber thieves and illegal miners becoming more common, said Nunes.

The rise in crime has been facilitated by drastic reduction in funding to Brazil’s environmental enforcement agencies, first under President Michel Temer, then with even more dire cuts under President Jair Bolsonaro. Last year’s budget to those agencies was the lowest in 17 years.

State environmental protections have also declined. In the last five years, Mato Grosso authorities guaranteed impunity to two out of five environmental offenders, including in cases of serious infractions, a recent study showed. This year alone, 1 million hectares of Amazon rainforest have already been devastated by illegal fires in Mato Grosso state.

“Our collaboration with local actors protects us,” Dugachard said, when asked about the risks posed to the farm by the rising wave of environmental crime in the region. “But these are lands where the public power itself has difficulty with command and control, so it’s challenging.”

Izzo mentioned another major potential threat: Plans are underway to install a large hydroelectric dam on the Juruena River. If approved and built, its reservoir will likely flood both Indigenous lands and productive areas on the banks of the river — including parts of the São Nicolau Farm.

These threats point up a problem inherent in all carbon storage projects: While they can sequester a great deal of carbon over time, that stored carbon can return to the atmosphere due to environmental disruptions caused, for example, by sociopolitical upheaval.

Then there is the problem of scale. If these initiatives are to capture truly significant amounts of humanity’s CO2 emissions, reducing the existential threat posed by climate change, then they will need to be massively scaled up — and quickly. The hope is that the lessons offered by the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project can be applied across the country and the planet.

Banner image: Amazon rainforest in Brazil. Image by Rhett A. Butler.

Mongabay Series: Amazon Conservation

ONF Brasil inventaria estocagem de carbono nas árvores do PCFPO (Acervo ONF Brasil)

O levantamento é uma atividade anual realizada desde 2003 nos plantios do Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF (PPCFPO). O inventário de 2020 aconteceu entre outubro e novembro e avaliou as 419 parcelas permanentes do projeto. O objetivo da atividade é medir o carbono estocado pelas árvores plantadas e pela regeneração natural na área do projeto mediante o acompanhamento do crescimento das plantas.

“Com base nos dados do inventário é possível quantificar o carbono que nossas florestas podem estocar de um ano para o outro. Deste modo, é possível argumentar sobre a importância de manter essas florestas em pé e quantificar qual o valor das nossas florestas para o mundo”, explicou um dos integrantes da equipe do inventário, o engenheiro florestal Roniel Lobo da Silva.

Os colaboradores da ONF Brasil foram organizados em equipes com a liderança de engenheiros florestais auxiliados por dois estagiários também de Engenharia Florestal: Marcos Vinicius da Unemat (Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso) e Mateus Rosante da UTFPR (Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná) e dois assistentes de campo. O Roniel e o Antonio Gomes do Nascimento Junior (estudante do último ano de Engenharia Florestal na Unemat) foram líderes de campo e assumiram a função de atuar na linha de frente, operando os equipamentos e testando nova ferramenta de coleta de dado me campo durante o inventário.

As equipes medem as árvores e inserem os dados no sistema (Acervo ONF Brasil)

De acordo com a metodologia da atividade, cada equipe vai a campo com as fichas do ano anterior – tendo acesso aos dados históricos – e coleta os novos dados da remedição das árvores. Este ano, a novidade foi o uso de tablets, garantindo a informatização dos dados. A tecnologia facilita o levantamento dos dados, minimiza os erros e torna as informações mais confiáveis. Para isso, foi desenvolvido um programa com o apoio da ONF International que permitia já inserir os dados diretamente no sistema.

Durante o inventário, são coletados dados de CAP (Circunferência à Altura do Peito), qualidade de fuste, tipo de fuste, além de informações mais detalhadas, como a presença de cipós ou ataques de pragas e doenças. Também são registradas as informações espaciais de acordo com o GPS do tablet.

De volta ao escritório, os dados coletados no dia são centralizados e salvos diretamente no banco de dados da Fazenda. A organização sistemática dos dados históricos no banco de dados e sua espacialização permitirá realizar análises muito mais profundas e multivariáveis sobre as dinâmicas de crescimento e estocagem de carbono das diferentes espécies plantadas em diferentes condições. Também garante uma maior qualidade e coerência de dados.

O Antonio destacou as facilidades do tablet. “Como a gente tem tudo georreferenciado e sabemos onde estamos, fica muito mais fácil de se localizar no mapa e nas parcelas da Fazenda”.

Outra novidade do inventário foi a participação do Luís Henrique de Araújo, estudante de 19 anos que cursa Engenharia Florestal na Unemat. Diferente de outros estagiários que já integraram as equipes da ONF Brasil, o Luís carrega consigo um diferencial: é fruto da Fazenda São Nicolau. Ele é filho do gerente de campo Gilberto de Araújo e da cozinheira Alaíde de Araújo, que vivem na propriedade e trabalham na ONF Brasil desde o início do projeto. Ou seja, Luís nasceu e cresceu na São Nicolau.

A decisão de cursar Engenharia Florestal aconteceu quando estagiários de pesquisa da UFMT (Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso) estavam na fazenda e o convidaram para ir a campo. “Eu percebi que realmente gostava de algo que estava envolvido com a natureza.”

Em 2020, suas aulas na Unemat foram suspensas por causa da pandemia. Achou melhor se deslocar de Alta Floresta para a Fazenda para ficar com os pais. Nesse período de isolamento, foi convidado para participar do inventário. Conta que foi a primeira vez que teve o contato direto com a coleta dos dados e seu tratamento.

Após o levantamento desses dados, o conteúdo é sistematizado em uma tabela de atributos e os dados podem ser extraídos e utilizados de acordo com o interesse da pesquisa ou projeto – auxiliando em atividades de pesquisa, florestais e agrícolas. É possível, por exemplo, avaliar o crescimento, a distribuição geografia das espécies e avaliar a regeneração. O objetivo principal, no entanto, é computar os dados para estimar o carbono estocado e gerar créditos de carbono, validados pela certificadora VCS (Verified Carbon Standard). Os créditos de carbono assim gerados podem ser comercializados e a receita obtida reinvestida no projeto. Neste ano especificamente, a venda dos créditos de carbono garantiu o equilíbrio econômico do projeto, cobrindo as perdas devidas à paralisação das atividades próprias da Fazenda por conta da pandemia, como ecoturismo e exploração da Teca.

“Foi um inventário bem-feito e organizado. Com este inventário, foi possível a correção de alguns erros dos anos anteriores e, se continuar nesse ritmo, para os próximos anos, teremos cada vez mais dados apurados”, avalia Roniel.

Auditores visitam a Fazenda São Nicolau para certificar créditos de carbono (Foto: Acervo ONF Brasil)

De 3 a 7 de maio, uma equipe formada por especialistas da SCS Global Service e do Sysflor estiveram em Cotriguaçu-MT para conhecer e avaliar os resultados do sequestro de carbono nos plantios do Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal (PPCFPO). A iniciativa existe desde 1998 e realiza o reflorestamento de área antigamente desmatada da Fazenda São Nicolau, com a intenção de absorver o carbono e combater os efeitos das mudanças climáticas. O objetivo do projeto é de absorver 1 milhão de tonelada de CO2 pelo acúmulo de biomassa florestal com o crescimento das arvores plantadas até 2038. As empresas auditoras devem apresentar um relatório final com observações e oportunidades de melhoria para o futuro. A primeira impressão da avaliação do projeto em campo, no entanto, foi bastante positiva.

A SCS Global Service foi representada pela Dra. Letty Brown e a Sysflor pela Nayara Zamin, ambas engenheiras florestais. O Projeto já tinha sido validado pelo VCS em 2011 com uma primeira verificação da quantidade de carbono estocado e com emissão de créditos de carbono para comercialização no mercado voluntario (VCUs). Na época, foram emitidos 112.292 créditos VCUs e, desse total, 61.530 VCUs foram comercializados com o reinvestimento do valor no projeto.

Especialistas acompanham a medição das árvores (Foto: Acervo ONF Brasil)

As visitas em um projeto certificado VCS são previstas a cada 5 anos. O objetivo da auditoria deste ano foi a verificação, de acordo com as diretrizes do VCS (Verified Carbon Standard) para nova emissão de créditos, da quantidade de carbono estocado, calculada durante o inventário florestal realizado nos plantios em 2015. O projeto também passou por validação para receber a certificação socialcarbon, que avalia a sustentabilidade, a biodiversidade e os impactos sociais humanos e naturais da iniciativa. Essa certificação fornece oportunidades para envolver a comunidade no projeto e compartilhar os benefícios sociais e ambientais.

Com essa finalidade, o grupo acompanhou e verificou a metodologia usada durante a coleta dos dados em campo, a prática de sistematização e a computação do cálculo final de carbono absorvido. De uma forma geral, as empresas devem verificar a consistência do projeto, as práticas e metodologias de coleta e analise de dados e, então, emitir créditos de carbono gerados e contabilizados a partir do reflorestamento (VCS) e da certificação do projeto no padrão socialcarbon. O Sysflor ficou com a função específica de avaliar o componente social da iniciativa e, portanto, foram realizadas entrevistas com os atores, parceiros e beneficiários locais para entender a relação da ONF Brasil com as comunidades vizinhas e a sua atuação no desenvolvimento da região.

A visita foi acompanhada pela diretora da ONF Brasil, Estelle Dugachard, pelo engenheiro florestal e responsável técnico da Fazenda São Nicolau, Alan Bernardes, e pelo especialista em carbono da ONF International, Danny Torres. No final da visita, a equipe certificadora concluiu a avaliação com a apresentação de oportunidades.

A expectativa é que, até o final do ano, seja finalizado o processo de auditoria completo com validação e verificação dos critérios e indicadores, gerando emissão de novos créditos de carbono que podem se tornar fonte de cofinanciamento do projeto.

Plantios são monitorados segundo metodologia da ONF Brasil e ONF International (Foto: Alan Bernardes/ ONF Brasil)

A atividade faz parte do inventário anual dos plantios do Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF (PPCFPO). Conduzida na Fazenda São Nicolau, a iniciativa iniciou em agosto e deve ser concluída no inicio de setembro. Ao todo, serão monitoradas 420 parcelas permanentes, alocadas em 84 talhões do projeto. O método segue as regras definidas pelo protocolo dos plantios, elaborado em parceria pela ONF Brasil e ONF International e validado pela certificadora VCS (Verified Carbon Standard, pela sigla em inglês).

A prática do inventário existe desde 2003 e é uma forma de monitorar o sequestro de carbono alcançado a partir do reflorestamento com 50 espécies nativas. No período da seca, no qual é realizada a medição, algumas espécies perdem as folhas. Porém, durante o ano na Fazenda São Nicolau, a beleza das árvores enche os olhos de estudantes, colaboradores e pesquisadores. A atuação científica é central para o PPCFPO, executado pela ONF Brasil. Ambas as iniciativas nasceram com o propósito de testar o conceito de poço de carbono florestal, consagrado pelo Protocolo de Kyoto – cujo objetivo era combater a emissão de gases de efeito estufa.

O PPCFPO é uma experiência bem-sucedida para demonstrar que é possível reflorestar o território amazônico com espécies nativas e com resultados de estocagem efetiva de carbono a partir do crescimento das árvores. Os plantios iniciaram em 1999 e usaram 50 espécies de nativas (na grande maioria dos 2.000 ha de área de pastos degradados reflorestados) e apenas 2 exóticas (teca e jamelão) em talhões minoritários.

Anualmente o inventário ocorre em duas etapas. A primeira compreende a coleta dos dados em campo pela equipe da ONF Brasil e colaboradores. Cada uma das parcelas mensurada e delimitadas por lascas de madeira tem 1000 m2 (com dimensões de 50 m e 20 m). As mesmas árvores são mensuradas, de forma continua, com a coleta dos dados de CAP (Circunferência na Altura do Peito), altura e estado fitossanitário dos indivíduos que foram plantados pelo projeto.

A segunda fase do inventário prevê a sistematização dos dados em planilha e, posteriormente, a quantificação do carbono estocado por meio do software calculador Camara.

A atividade é realizada todos os anos e, em 2017, recebeu o apoio de 8 acadêmicos de Engenharia Florestal da Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso (Unemat), campus Alta Floresta. Os estudantes que participam do inventário têm a oportunidade de praticar em campo o conhecimento adquirido na academia. Neste ano, a Prof. Fabrícia Rodrigues foi responsável pela orientação e acompanhamento dos estagiários. Os alunos foram selecionados por meio de edital lançado pela ONF Brasil em junho. O estudante de mestrado em Ciências Agronômicas da Universidade Livre de Bruxelas (ULB), Clément Bocque, que atualmente coleta dados na Fazenda São Nicolau para o seu Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, também contribuiu com a atividade.

Veja mais fotografias do inventário:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clément, ao lado do Dr. João Ferraz, caminha pela Fazenda São Nicolau, em território amazônico (Foto: Roberto Silveira)

Clément Bocqué, estudante de mestrado da Universidade Livre de Bruxelas (ULB), chegou em Cotriguaçu (MT) em 17 de julho para acompanhar o Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF (PPCFPO) na Fazenda São Nicolau. O mestrando em Ciências Agronômicas se surpreendeu com a biodiversidade brasileira. “Muito do que estou vendo é novo e de tirar o fôlego”, diz. Ele conta que já sabia sobre o trabalho realizado na Fazenda e viu no estágio a oportunidade de conhecer de perto as atividades do Poço de Carbono. Esse programa de estágio obrigatório tem por objetivo proporcionar o contato do estudante com o trabalho realizado por empresas fora do meio universitário.

No Brasil, Clément é supervisionado pelos professores Dr. Roberto Silveira (Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso – UFMT), coordenador científico do PPCFPO, e Dr. João Ferraz (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia – INPA), presidente do Comitê Científico e Técnico do PPCFPO. O estagiário é responsável por verificar o crescimento de quatro espécies de árvores nativas nas áreas de reflorestamento do Projeto. A análise do desempenho dessas espécies deve considerar como possíveis fatores determinantes os tipos de tratamentos silviculturais, a composição de espécies plantadas em reflorestamentos mistos e as características do solo.

O mestrando celebra a oportunidade de entender melhor as pesquisas desenvolvidas na Fazenda São Nicolau e a dimensão do PPCFPO, que realiza trabalhos relevantes para seu campo de estudo. Durante o trabalho de campo, Clément deve se familiarizar com o método de coleta de solos, examinar os plantios e aprender a identificar algumas espécies plantadas. O estudante conta que as espécies de árvores, as plantas e o solo da região são muito diferentes em comparação com a Europa. “Enfim me dou conta da dimensão do Projeto e da quantidade de pesquisas feitas. Estou impressionado com a beleza do país, da natureza e da biodiversidade, especialmente para uma pessoa de Bruxelas, muito do que estou vendo é novo e de tirar o fôlego”, exemplifica. Todo o trabalho de campo – abrangendo 15 dias iniciais em Cuiabá, 2 meses e 10 dias na Fazenda São Nicolau e 3 semanas novamente na capital mato-grossense – tem final previsto para 3 de novembro.

Clément e o Dr. João Ferraz durante o trabalho de campo na São Nicolau (Foto: Acervo ONF Brasil)

Indivíduo macho do H. peugeoti com coloração vermelha (Foto: Museu Nacional com edição de Eduardo G. Baena)

A espécie Hyphessobrycon peugeoti possui como características gerais o padrão de cor vermelha no indivíduo adulto e uma barbatana dorsal alongada nos machos. A identificação ocorreu a partir de pesquisas realizadas durante alguns anos no Rio Juruena – que se encontra com o Teles Pires e forma o Rio Tapajós. A Hyphessobrycon peugeoti é similar à Hyphessobryco loweae, proveniente da bacia do Xingu. O grupo de pesquisadores da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES) e da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) liderados pelo curador da coleção ictiológica do Museu Nacional, o Dr. Paulo Buckup (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ), elencaram os atributos da nova espécie em artigo de 2013. O Dr. Paulo Buckup também é membro, desde 2006, do Comitê Científico e Técnico do Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF, cuja finalidade é orientar as pesquisas técnicas e científicas realizadas no Projeto. Hyphessobrycon peugeoti foi a primeira espécie nova descrita como fruto dos esforços em pesquisa do Projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot ONF-Brasil.

O paper também realiza uma análise comparativa entre a H. peugeoti e a H. loweae. Em vez da coloração amarelada no indivíduo maduro, a H. peugeoti é vermelha. Além disso, enquanto a H. peugeoti tem cinco séries de escamas horizontais em sua lateral, a H. loweae tem entre seis e sete. A quantidade de raios ramificados na nadadeira anal também é maior na H. peugeoti.

Das demais espécies do gênero Hyphessobrycon, o peixe recém classificado se diferencia pela barbatana dorsal alongada em filamentos e a borda praticamente reta da terminação da barbatana anal. Inserido na família Characidae, o gênero em questão está entre os mais ricos, com 125 espécies válidas.

O gênero Hyphessobrycon não é monofilético: as espécies não possuem um ascendente em comum. Em vez disso, ele é formado, em menor quantidade, pelo agrupamento de espécies relacionadas ao gênero Astyanax (aquele do peixe lambari) e, em maior quantidade, pela mistura de espécies dos gêneros Hemigrammus, Pristella, Thayeria, Paracheirodon e Hasemania.

Dessa maneira, há controvérsias sobre a delimitação de algumas espécies no Hyphessobrycon, principalmente em relação ao Hemigrammus (aquele dos peixes de aquários) – visto como um possível sinônimo. Logo, os estudiosos apontam a necessidade de mais estudos para desfazer a polêmica e melhor identificar a espécie H. peugeoti, atualmente localizada no Hyphessobrycon.

Os espécimes analisados de H. peugeoti foram coletados na seção intermediária do Rio Juruena, na parte superior da bacia do Tapajós, em regiões rasas (com até um metro de profundidade) e no período inicial da seca. O nome para a classificação científica foi inspirado na família Peugeot, que, por meio da montadora de carros, conduziu à elaboração e execução do projeto Poço de Carbono Florestal Peugeot-ONF na Fazenda São Nicolau em Cotriguaçu (MT).

Referência bibliográfica:

Ingenito, L. F., Lima, F. C., & Buckup, P. A. (2013). A new species of Hyphessobrycon Durbin (Characiformes: Characidae) from the rio Juruena basin, Central Brazil, with notes on H. loweae Costa & Géry. Neotropical Ichthyology, 11(1), 33-44.